Mesothelioma often arrives like a letter postmarked in the 1970s that doesn’t hit the mailbox until the 2020s. That “long latency” isn’t a coincidence or a paperwork glitch—it’s baked into the biology of asbestos fibers and the slow, cumulative way they injure tissues over time. Understanding why the disease takes decades to surface isn’t just academically interesting; it directly shapes medical decision-making and the legal timelines that govern compensation. This piece explains, in plain English, how fiber “biopersistence” drives latency and how statutes of limitation, discovery rules, and early testimony preservation intersect with that biology.

The biology behind the delay: biopersistence and slow burn injury

Asbestos fibers are thin, needle-like crystals. When disturbed, they become airborne and easily inhaled or swallowed. Some reach the deep lung, then migrate to the pleura (the thin lining around the lungs) via the lymphatic network. Others can reach the peritoneum (the abdominal lining). What happens next is slow and insidious. The immune system tries to engulf the fibers—macrophages attempt to “eat” them—but because the fibers can be long and rigid, the process stalls (“frustrated phagocytosis”). That stalemate chronically releases inflammatory chemicals and reactive oxygen species—tiny sparks that can damage DNA, disrupt cell signaling, and gradually push cells toward malignant transformation.

Not all asbestos behaves identically. Amphibole fibers (like crocidolite and amosite) tend to be more durable—more “biopersistent”—than serpentine fibers (like chrysotile). Greater durability means fibers remain in tissues longer, stoking inflammation for years. The result is a slow, stepwise accumulation of cellular hits: a mutation here, a chromosomal misstep there, epigenetic changes that alter gene expression. Over 20–50+ years, those changes can culminate in mesothelioma. In short: the disease isn’t “sudden.” It’s the final chapter of a very long story.

Dose matters—but there’s no safe level

High-intensity exposure (e.g., shipyard insulation work in confined spaces) often shortens latency; lower, chronic exposures (including para-occupational “take-home” dust from a family member’s work clothes) may lengthen it. But “longer” doesn’t mean “safe.” Mesothelioma has been documented after comparatively modest exposures. Genetics can also influence susceptibility. Rare alterations—for example in BAP1—appear to raise risk and may shift latency, which is why a careful family and personal cancer history helps clinicians decide whether genetic counseling is appropriate. The practical takeaway for patients and counsel alike: don’t discount exposures just because they were brief or happened outside an industrial setting.

Why diagnosis often arrives late

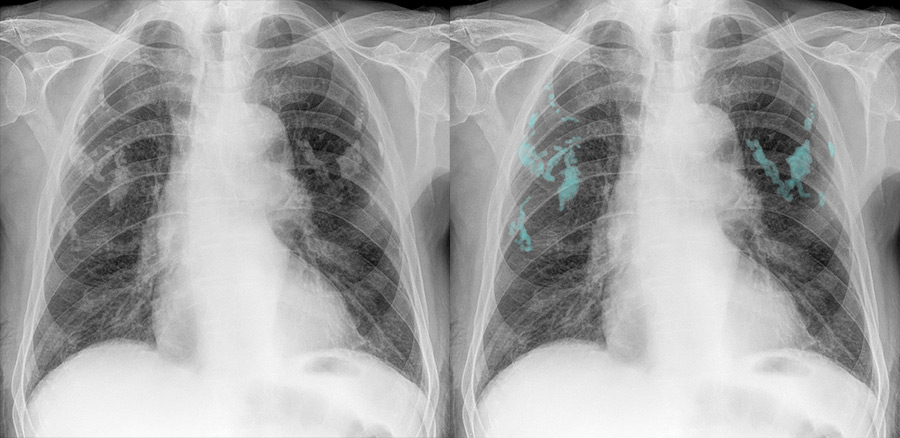

The same mechanisms that make disease slow to develop make it easy to miss early. Initial pleural changes can be subtle; symptoms—shortness of breath, chest discomfort, fatigue—mimic far more common conditions. People and providers may attribute early problems to age, smoking history, or ordinary heart–lung disease. Imaging evolves gradually from nonspecific pleural thickening to concerning nodularity or effusions. By the time biopsy confirms mesothelioma, decades may have passed since the exposures that caused it. That timeline drives both medicine and the law: clinicians have to look backward for exposures the patient barely remembers, and lawyers have to fit a 40-year story into rules written for much shorter disputes.

Legal clocks 101: statutes of limitation, discovery rules, and statutes of repose

In most jurisdictions, a statute of limitations sets the filing deadline for personal-injury claims—often one to three years. The clock usually starts at diagnosis or when the person “knew or should have known” that their illness might be related to asbestos (the discovery rule). That language matters. Because mesothelioma is strongly associated with asbestos, the diagnostic moment typically triggers the limitations period. For families, a separate wrongful-death statute applies, with its own clock starting at death.

Some states also have statutes of repose—absolute deadlines measured from the defendant’s last act (for example, the date a product was sold or a building was completed), regardless of when the injury is discovered. A statute of repose can cut off claims even before disease appears. Many jurisdictions carve out exceptions for latent toxic exposures or for asbestos specifically, but the details vary. The practical advice: do not wait. As soon as mesothelioma is suspected (even before final pathology), consult counsel who knows the local rules; choosing the right forum and filing quickly can be outcome-determinative.

The two-disease rule and prior non-malignant diagnoses

Many states recognize a “two-disease” or “separate-disease” rule: a prior diagnosis of an asbestos-related non-malignant condition (like asbestosis or pleural plaques) doesn’t start—or exhaust—the limitations period for a later cancer claim. That protects patients who were diligent years ago but later develop mesothelioma. Still, because rules differ and older settlements may include releases, lawyers need to review prior paperwork carefully.

Trust claims, workers’ compensation, and VA benefits—parallel but different clocks

Asbestos bankruptcy trusts (established by former manufacturers) have their own filing criteria and deadlines, typically keyed to the date of diagnosis and supported by medical and exposure evidence. Workers’ compensation systems are administrative, with notice and filing deadlines that can be much shorter than civil statutes. Veterans may have service-connected exposure routes (e.g., shipyards, boiler rooms, pipe-fitting on vessels); VA benefits aren’t subject to the same statutes of limitations, but earlier filing helps secure care and compensation sooner. Coordinating these avenues matters because payments can offset one another and liens (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers) must be honored.

Why speed is a medical–legal imperative

Mesothelioma can progress quickly. As treatment begins, patients may face fatigue, procedures, and the sheer cognitive load of illness—none of which favor detailed memory work. That’s why early action is key on two tracks:

- Clinical documentation. Clinicians should capture a structured exposure history at the first serious suspicion: job sites, roles, specific dusty tasks, brand names where remembered, dates, and whether protective equipment was used. Pathology reports (including immunohistochemistry), imaging, procedure notes, pulmonary function tests, and performance status belong in a single, well-organized packet. That record supports treatment and becomes the evidentiary spine of any legal claim.

- Preserving testimony. Attorneys can promptly arrange a preservation (de bene esse) deposition—often videotaped—so the patient’s story is captured under oath while they’re able to testify. Many courts offer trial preference or accelerated settings for terminal illness or advanced age; counsel should invoke those mechanisms early. Affidavits from coworkers and family members who handled laundry or shared vehicles can fill in the “take-home” and product-identification gaps. Employment records, Social Security earnings statements, union cards, and military service records help anchor dates and sites.

Common pitfalls—and how to avoid them

- Vague exposure histories. “I did construction in the ’70s” won’t satisfy the legal standard in most courts. Concrete details—“I removed pipe insulation in the turbine building at X power plant, cutting amosite lagging and scraping gaskets in visible dust”—are persuasive.

- Missed forums and deadlines. Waiting for a final PET scan or a second opinion can burn precious weeks. File to preserve rights; you can supplement medical records later.

- Inconsistent narratives across filings. Trust submissions, workers’ comp forms, and civil complaints must harmonize. Inconsistencies invite challenges.

- Overlooking para-occupational and environmental exposures. Family laundries, home brake jobs, and apartment renovations are real exposure routes—ask, document, and corroborate.

A practical division of labor

Clinicians don’t need to practice law, but they can write notes that are medically rigorous and legally usable: clear diagnosis, differential reasoning, staging, symptom burden, and a chronological exposure narrative. Lawyers don’t practice medicine, but they can move fast to preserve testimony, gather records, and select viable defendants and trust paths. Both can counsel families on immediate steps that matter: avoid further exposure (e.g., unsafe home renovations), keep a symptom diary, and save every document—pay stubs, union newsletters, jobsite photos, even old tool receipts.

Bottom line

Mesothelioma’s latency is the predictable outcome of fiber biopersistence and a slow, inflammatory injury that unfolds over decades. The law tries to account for that with discovery rules and separate-disease doctrines, but it also imposes unforgiving clocks. The winning strategy—medically and legally—is to act early, document thoroughly, and preserve testimony while the patient can speak for themselves. Biology sets the long fuse; smart, prompt action keeps the fuse from burning out the claim.